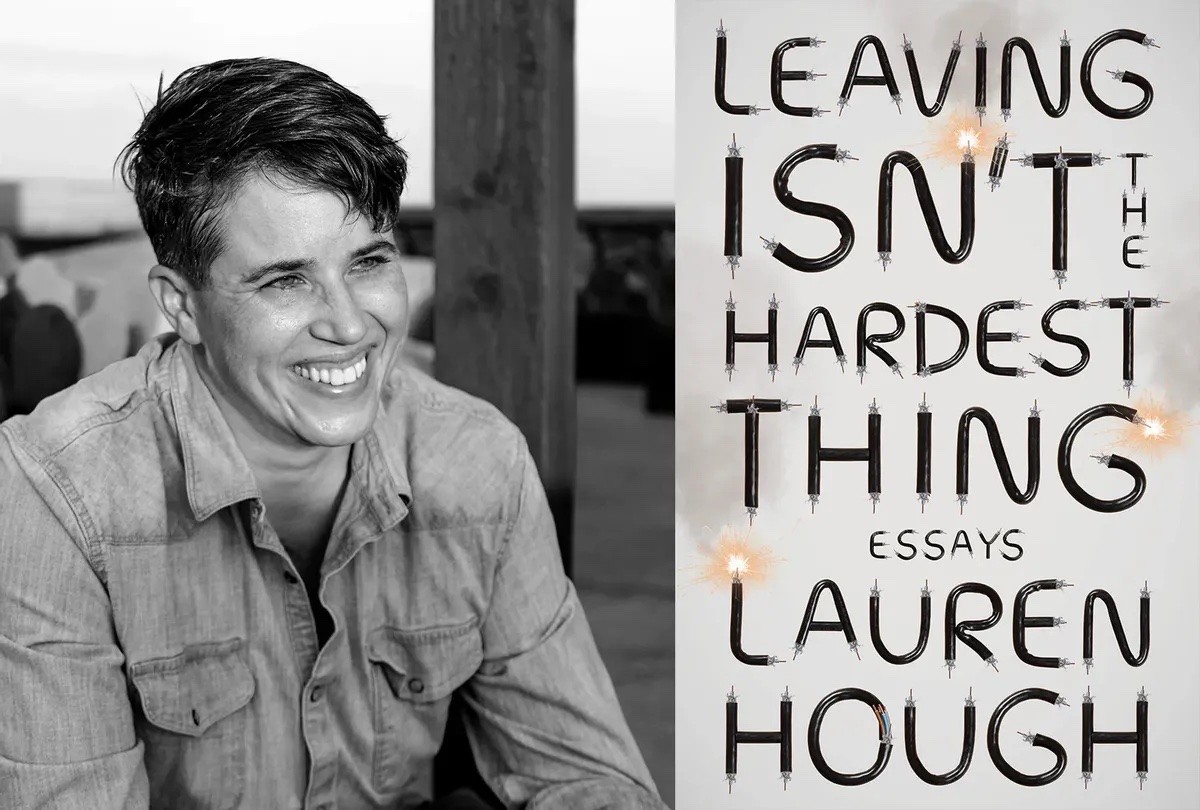

Leaving Isn’t the Hardest Thing, Lauren Hough’s new essay collection, is a tough read. In every sense.

The 11 essays themselves are tough—Hough has lived a life that has inured her to the usual bullshit with which we all struggle. Among other things, she grew up in the Child of God cult; joined the air force as a closeted lesbian during Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell; worked as a bouncer at a gar club in early aughts D.C.; spent a terrifying span of time in jail without her meds or glasses; and worked a series of blue-collar jobs that are rarely portrayed as vividly as in these stories.

And the book itself is difficult to read. Hough is a cool narrator (as in, one can’t help but imagine her watching your reactions to her tales from behind a cigarette squint), and she isn’t interested in providing life lessons or silver linings from something like her decade spent as a cable guy. But if she’s hard on the reader, as in the final essay in which she calmly enumerates the items that comprise the American dream and in the process reveals them to be shallow, consumerist groupthink, she’s just as hard on herself.

Hough has spent too many years as a bartender to succumb to cheap sentimentality, and Leaving Isn’t the Hardest Thing has all the earmarks of Joan Didion’s icy gaze with none of the navel-gazing. If she interrogates her own emotional and mental state, it’s only to put into context the life that she’s led, one predicated on the simple belief instilled in her as a cult member that she was never good enough.

Novelist Garth Greenwell on the Eroticism of Frustration and Gratification

There’s a fatalist quality to the best (and most difficult) chapters, never more than in “Cell Block,” detailing her time in jail after assaulting her girlfriend’s lover. As it turns out, that lover was friends with the local police force, and they went all out in taking care of their friend, as Hough’s expense. Her unwavering, staccato recount of losing time in a windowless cell is harrowing precisely because you already know from the preceding chapters that there will be no happy ending to the story. There will only be survival. (Hough would no doubt smile grimly were she to know that I had to keep walking away from that chapter before I could finish it.)

How Many of These 2021 Lammy Finalists Have You Read?

If all of this makes the book sound bleak, well, it kind of is. But there’s a grace to Hough’s dry writing style that prevents the book from ever becoming a chore. Any triumphs she has enjoyed in her life (and the final chapter is, in many ways, the most triumphant, even as she effortlessly explains that she left the Child of God cult only to find solace in America, maybe the biggest cult of all) have come at a cost. We’re lucky to have her retelling of that cost. And more importantly, that she retained enough wit and sardonicism to tell us these stories in the first place.

Oh and the next time you have a cable guy in your home? Offer them the bathroom.