Dating a wealthy older man is almost a rite of passage for 20something gay men. If you’re lucky, the power imbalance eventually morphs from sexually charged into that of a mentor, one who welcomes you into a half-lost world of taste and experience and opportunities.

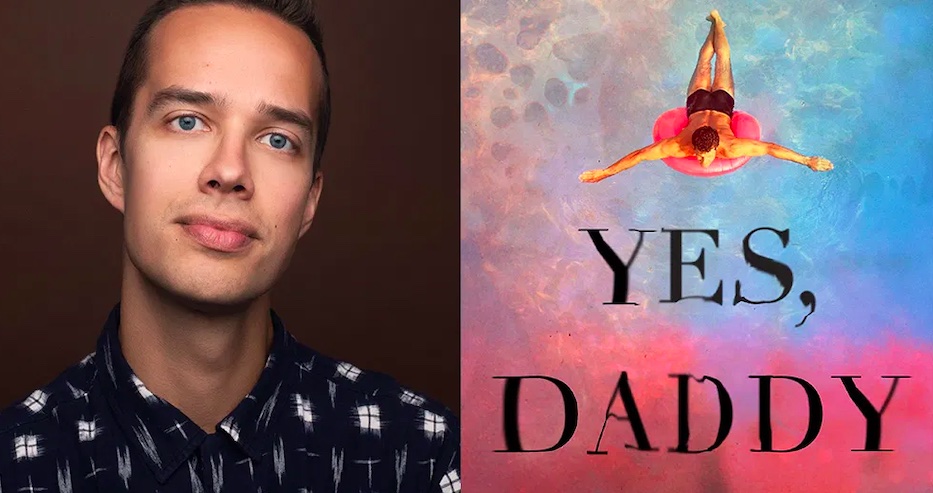

If you’re very, very unlucky, you’re one of the boys in Jonathan Parks-Ramage’s new novel Yes, Daddy.

Yes, Daddy begins, as most horror stories do, with a man unwilling to closely examine the opportunity that promises to save him from his current untenable situation. Jonah is an aspiring playwright with the student debt and excruciating survival job to prove it. He’s also ripe for the plucking for an older man like acclaimed playwright Richard: He has serious daddy issues; he’s no longer speaking to his mother; and he’s desperate for any toehold into the life his good lucks and muscular body could provide.

Jonah is a little bit of a mercenary, but no more so than Holly Golightly.

That his careful plans pay off—research on Richard’s likes and dislikes, a planned meeting, a very expensive outfit to indicate he’s not a gold digger—is not surprising. The world of Manhattan in the aughts is so carefully recreated Yes, Daddy can sometimes feel like reportage, and Jonah’s scheme is of a piece with it.

That Jonah’s careful plans do not include Richard’s own wants and desires is a new wrinkle—and a horrifying one for anyone who has ever gamely reached for his wallet at the end of an extravagant meal, only to sink back in relief when his host waves him away. And Parks-Ramage has gleeful fun in creating an all-too-believable alternate reality for what happens to boys like Jonah when the bills comes due in the no-consequences world of gay celebrity. Critics have likened the book to Get Out but the pop culture reference to which I kept returning is Burnt Offerings. As in that gothic thriller (especially the film adaptation, featuring forever daddy Oliver Reed), it behooves one to at least toss a cursory glance at a gift horse’s mouth, before that horse eats you alive.

Along the way, Parks-Ramage offers up cutting portraits of everything from the homogenous wait staff at a popular Chelsea eatery (a survivor of the era, I immediately pictured Cafeteria) to the manufactured competition into which younger men dating older men automatically fall when around one another. Not to mention the constant uncertain toehold the younger man possesses in every May-December relationship. Sex may be the great equalizer, but that extends just as far as the bedroom. You’re always a step away from being slapped back down depending on daddy’s mood, and Jonah seems particularly ill-suited to those power games.

That detailed web of Jonah smugly finding a place for himselfwith Richard’s friends on Richard’s Hamptons compound, is also a reason the novel begins to unravel in its final quarter. Parks-Ramage speeds through years in the final chapters, creating a dizzying series of false endings that feel like attempts to squeeze in a few more acid-dipped darts at everything from social justice warriors to #MeToo coverage to the culture of blind-eye turning and silence that allows men like Richard to continue unabated. By the time there’s a suicide and an attempted murder and Jonah simply keeps returning to NYC as if life anywhere else is unthinkable, Yes, Daddy begins to feel like an edging session that’s extended just a bit too far. You start thinking less about the climax and more about how much time you can devote to this before finally getting up and starting dinner.

But if, as with sex, the journey is more fun than the eventual destination, there’s a hell of a lot of pleasure to be enjoyed at Parks-Ramage’s hands. And hopefully a lot more to look forward to from this first-time novelist.

Get real time update about this post category directly on your device, subscribe now.