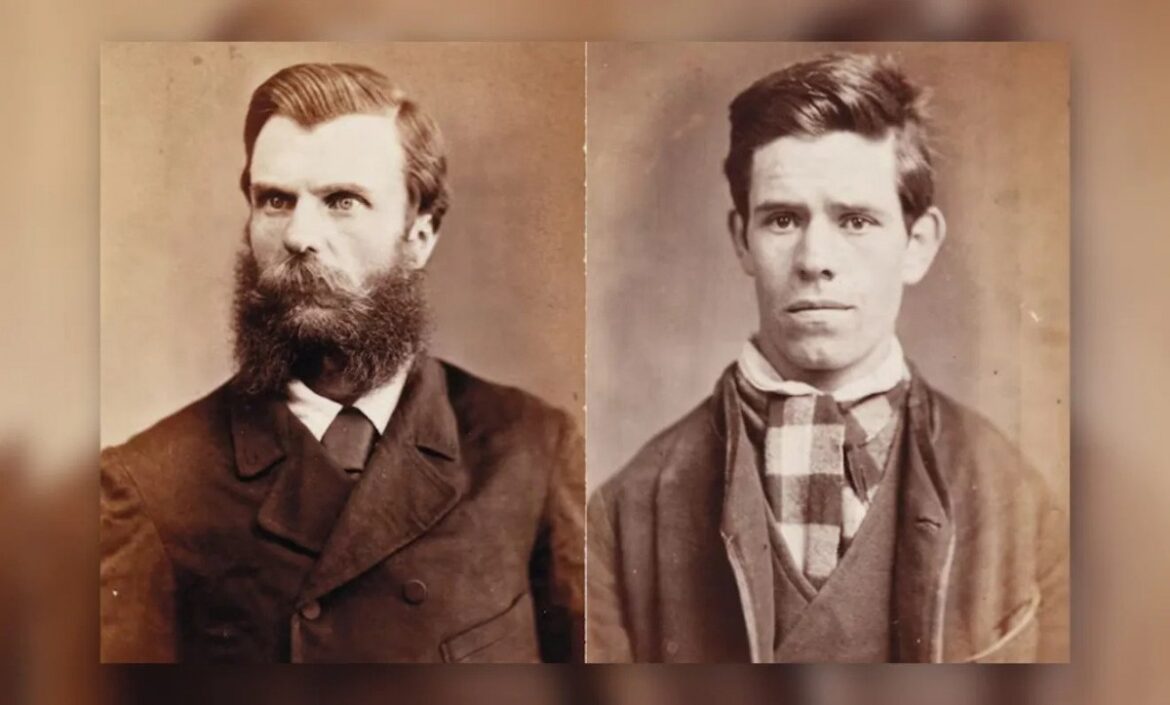

The Australian bushranger is the stuff of colonial legend. Analogues to the highwaymen and outlaws of the American Old West, these highly romanticized villains became folk heroes, symbols of rebellion, and Australian national pride. To this day, the most famous and iconic bushranger Ned Kelly lives on in the national consciousness of Australia and even was the subject of the world’s first dramatic feature-length film “The Story of the Kelly Gang” in 1906. But more relevant to the interests of this site, and to queer history, is his contemporary: Captain Moonlite.

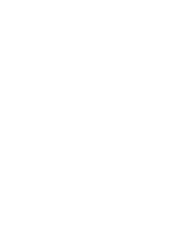

William Strutt’s “Bushrangers on St Kilda Road” painted in 1887, seven years after Captain Moonlite and Ned Kelly were executed thus ending the age of the bushrangers. (Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of Melbourne)

Andrew George Scott—aka Captain Moonlite—was similarly infamous. But for the longest time, Captain Moonlite’s legacy was almost forgotten until 1995 and the unique story of Australia’s gay bushranger became a new symbol of rebellion for Australia’s queer community.

Note: Archaic spelling of the word jail in Australian English is ‘Gaol’. I have kept this spelling for the proper names of the various prisons.

The Life of the Gay Bushranger

Andrew George Scott was an Irish-born immigrant from New Zealand who arrived in Melbourne, Australia after serving in the New Zealand Wars with the colonial army. Son of an Anglican clergyman, George (as he had preferred to be known as) intended on entering the Anglican priesthood. Contemporarily described as passionate with a tendency to violence, George started as a bushranger in earnest with a late night robbery of the local bank of Mount Egerton (where he had currently lived.) In true bushranger fashion, he asked the bank manager how much he himself had deposited. On hearing the sum, George withdrew the amount and handed it to the manager. He left a note absolving the manager of blame and signing himself as Captain Moonlite.

After a series of cons and thefts, George was finally up on trial for the Mount Egerton theft. Although a consummate orator and operating as his own defense counsel, the evidence was too great and with the amounts of witnesses stating they had been swindled by George, he eventually was sent to prison. After escaping the “inescapable” Ballarat Gaol, he was eventually sent to Pentridge Prison.

Pentridge Prison as it currently looks. The prison operates as a museum. The prison grounds are currently proposed to host a residential village, a controversial decision. (National Trust of Australia)

Pentridge was notoriously brutal even by contemporary standards. The abject cruelty of the guards was a constant terror to George and his fellow inmates. However, in the horrors of prison life is where he met his soul mate: James Nesbitt.

James meets the Captain

His polar opposite, James came from a poor working-class background with an abusive father. He was softer-spoken and more level-headed than George and had been imprisoned for a series of petty thefts. The couple were constantly separated to “preserve discipline” and, in an odd bit of punishment, one day was added to James’ sentence for bringing George a cup of tea. When George was released in 1879, James was waiting for him, having been released himself a year previously.

RELATED LINK: Un Chant d’amour (1950) is the Proto-Gay Porn Film

It was looking to be a happy future. The infamy that George had gained as ‘Captain Moonlite’ allowed him to hit to give lectures on prison reform. Although initially successful, the infamy he gained was a double-edged sword: he was constantly brought in for questioning by police for crimes he couldn’t have committed, and was warned off further employment by the police. He was harassed so brutally and in the end was sick with pneumonia with no funds for treatment.

The Wantabadgery Bushrangers

It was then that George decided to live up to his name. Previously more hustler than highwayman, George assembled a group of young men to go out in the bush to find work. After crossing the border into New South Wales from Victoria, the gang confined and robbed the Wantabadgery Station holding twenty-five people hostage after being refused work, food, or shelter from the owner. Close to starvation, they were desperate and willing to do whatever they could.

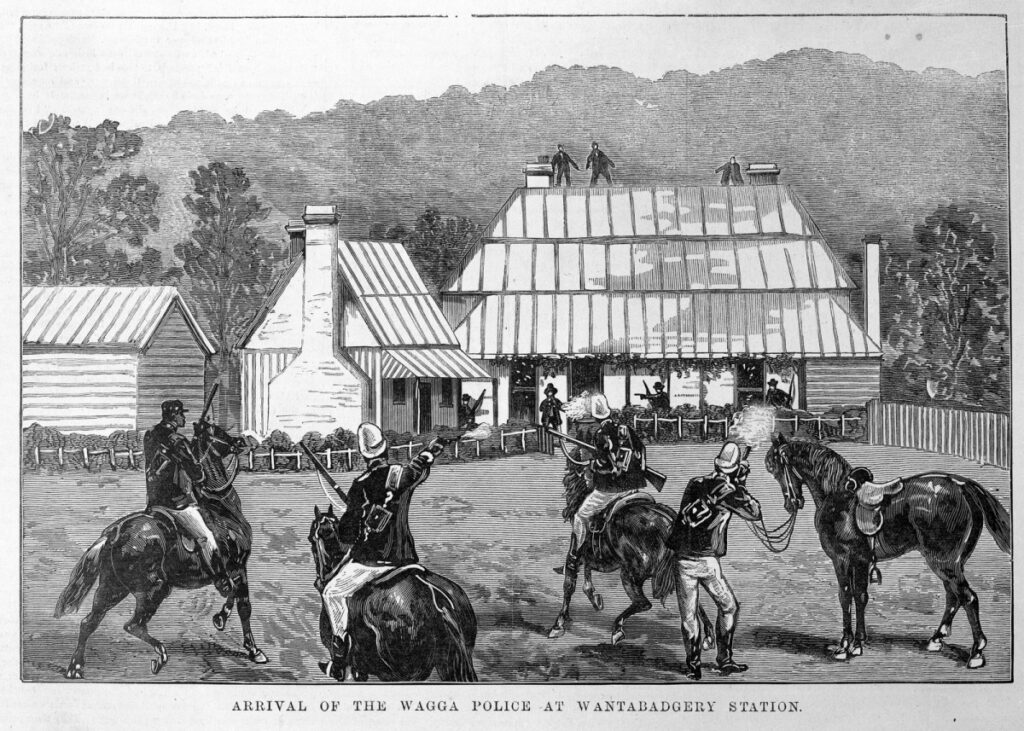

A news illustration of the arrival of the Wagga Police to Wantabadgery Station. (State Library Victoria)

Now known as the Wantabadgery Bushrangers, the hold-up of the station was eventually communicated to the local mounted troopers who finally cornered the gang holed up in a farmhouse. It was here, in the brief and bloody gunfight, that James was shot in the head. George “wept over him like a child, laid his head upon his breast and kissed him passionately.” The shooting of a constable was what sealed George’s fate, although it is unlikely he shot the policeman. He was sentenced to hang.

In his final days, George wrote to James’ mother. He sent her a lock of her son’s hair, signing the letter “ever to you, your loving son in spirit.” He then requested in his letters to be buried next to James in the Gundagai cemetery. Approaching the gallows, George twisted the ring he always wore made of James’ hair. His death was quick and exhibited in front of 4000 people.

…to be buried beside my beloved James…

His final wish he stated was: “…to be buried beside my beloved James Nesbitt, the man with whom I was united by every tie which could bind human friendship, we were one in hopes, in heart and soul and this unity lasted until he died in my arms.” Sadly this wish was not granted and George was interred at Rookwood Cemetery over 100 kilometers away from James’ final resting place in Gundagai.

The Grave of the Gay Bushranger

In 1995 however, Christine Ferguson, the former president of the National Party (a regional interest center-right political party and member of the Liberal-National Coalition) and Samantha Asimus decided to get the body exhumed and reburied next to James Nesbitt as was George’s final wishes.

“He was educated, he was articulate, he was a poet, an engineer, a sailor, an excellent horseman, skilful in firearms and also quite spiritual,” Samantha told the Canberra Times in 1995.

But before we start applauding this: to these women, this was merely an interesting project about another bushranger. For Christine particularly, the idea of Captain Moonlite being in a same-sex relationship with James Nesbitt was not relevant.

“He actually didn’t say that [he loved James]”, Christine said to Jeff Sparrow of The Monthly in 2015. “Well, he did say it – in a way. But it was a long time ago, and mates were mates. We don’t know if he was gay or not. It comes down to your interpretation of ‘mate’ and what ‘mateship’ would have meant at the time.”

“Gundagai is conservative but I don’t think it’s really bothered by homosexuality.”

They’ll Celebrate The Idea, Not The Reality

Even with the letters and tourist potential, Christine was insistent that Captain Moonlite’s queerdom would not be celebrated in the town.

“No, I didn’t think Gundagai would be into that. A lot of the old people want to keep Gundagai how it is and how it has been in the past… They’re not very progressive.”

The goal posts for indicating queerdom in our historical figures seem ever changing, and for the proof to be overwhelming to the point of monotony. Even in his own letters, George expressed his undying love for James. But to people like Christine, its still not enough.

A common trope nowadays in the assumption of heterosexuality, or if any same-sex attraction was visible, it was in a homo-social environment bereft of sexual or romantic desire and purely under “friendship” or “mateship”. The coded language is akin to the suppression of Golden Age of Hollywood’s Cary Grant cohabiting with fellow actor Randolph Scott as “confirmed bachelors”. The desire to squash all homosexuality from history (particularly within the past 200-300 years) is one of the many micro-aggressions we see as queers. Our histories are papered over and homogenized to remove illicit love. In the shade of secrets, shame blooms eternal.

Gundagai’s Shared Grave

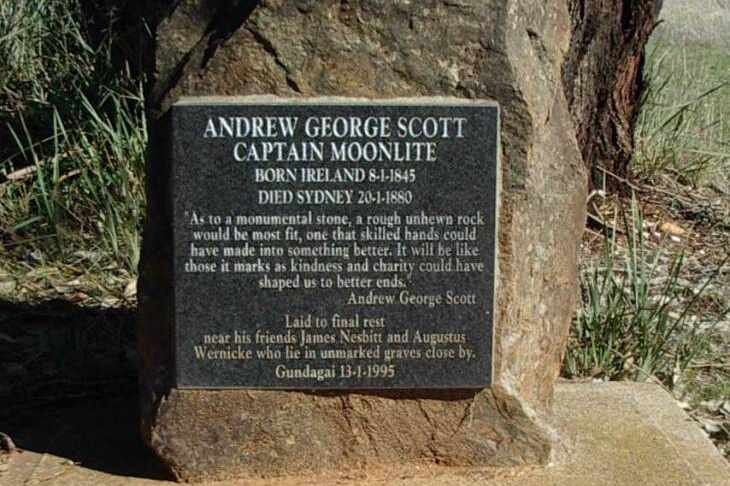

If you happen to visit Gundagai, you’ll find the joint tombstone of James Nesbitt and Captain Moonlite. In death, they are united as George had asked. It is a bittersweet reality that the epitaph he requested is not on display. It was to read:

“This stone covers the remains of two friends. James Nesbitt, Andrew George Scott. Separated 17 November 1879. United 20 January 1880.”

The date they were separated was the date of James’ death. When they were united was when George himself was executed.

Captain Moonlite’s Grave marker. Augustus Wernicke was another member of the Wantabadgery Bushrangers who died in the same gunfight as James Nesbitt. (Visit Gundagai)

Sources: ArtsHub, Canberra Times, Ian Potter Museum of Art, In Search of Captain Moonlite by Paul Terry, The Monthly, Moonlite by Gary Linnell, Museum of History New South Wales, National Trust of Australia, State Library Victoria, Visit Gundagai

Get real time update about this post category directly on your device, subscribe now.