Welcome to The (Book) Club, where we talk about gay male fiction and nonfiction that needs to be on your radar.

I have a longstanding love of both Jean Smart and the Lifetime network, which is why I will never forget the time in 1998 when both of them let me down. That’s the year Lifetime released Change of Heart, starring Ms. Smart as a woman whose perfect life is torn apart when she discovers her husband is gay. And because ’90s-era Lifetime was obsessed with women in peril, this was treated as a tragedy on par with a nuclear bomb going off in a Talbot’s.

A similar shudder went through my high school when a classmate’s father revealed he was gay, divorced his wife, and moved to Florida with his male partner. The gossip around school—and I heard it from teachers as well as students—was about how tragic it was for the wife and how monstrous the husband was for abandoning his family.

And… sure. It is absolutely devastating when a marriage ends. It’s terrible to learn your spouse—whether on Lifetime or in real life—has been hiding something from you. It’s destabilizing to discover a lie has been woven into your daily existence.

But it’s also devastating to live in a homophobic society that forces gay men to perform a false heterosexuality instead of simply living as themselves. Isn’t the saga of the “sham straight husband” just as hard for the man as it is for the woman? Aren’t there two people suffering in this scenario? Back in the ’90s, I was incredibly disappointed that the rhetoric always discarded the humanity of the closeted gay man, and ever since, I’ve been looking for stories that acknowledge it.

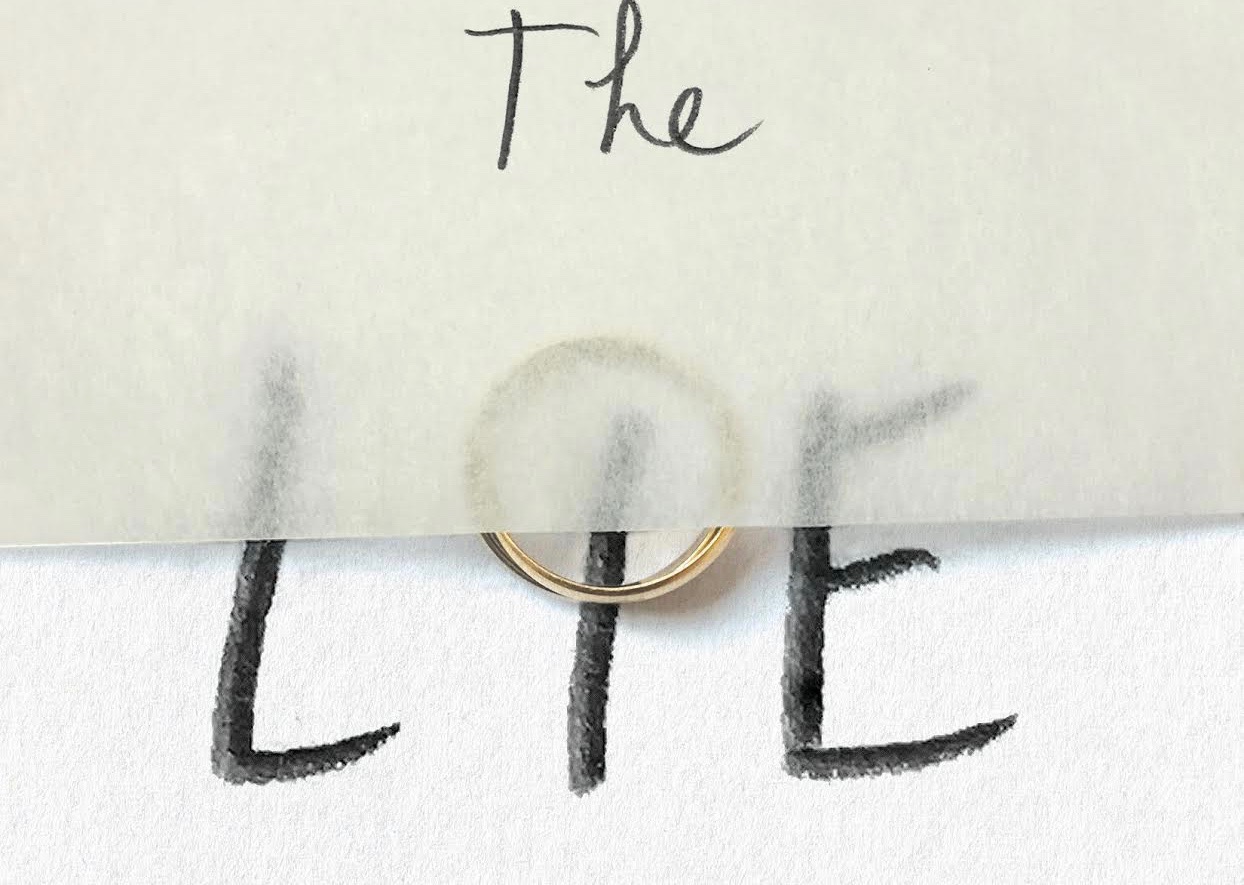

That’s why it was such a treat to read The Lie, William Dameron’s beautiful memoir about his heterosexual marriage and his decision to come out in his mid-40s.

Dameron writes especially well about his genuine love for his wife, and how much it tore him apart to gaslight her for decades as she kept sensing that something was wrong. His willingness to accept his own failures toward this woman—and their two daughters—is unvarnished and clear-eyed, and his moral clarity makes it easy to trust him as a narrator.

He’s also just easy to like. When he’s writing about his first fumbling gay kiss as a teenager or his unexpected love for the family dog, he comes across as someone who has managed to maintain a capacity for joy, despite his dark years abusing Valium and steroids in an effort to numb his own self-loathing. When he writes about his desire to emulate his straight, older brother or his tentative first dates with the man he will later marry, he communicates his feelings with a potent present-moment urgency.

And when Dameron’s breakthrough finally arrives—when he finally starts allowing himself to be known—he gets at the mixture of glee and terror that always accompany coming out. Even though I was lucky enough to be able to come out as a teenager, I still remember how it felt, and I’m grateful to Dameron for reminding me that the experience is the same for all of us, no matter how old we are when it happens.

Meanwhile, he frames his book with another true story: Apparently, people all over the world have used Dameron’s photo to catfish straight women online. He is regularly contacted by ladies he’s never met who think they’ve been falling in love with him via IMs and emails. It’s a remarkable coincidence that adds even more heft to his own coming out, because it reminds us that the truth is often elusive. What matters is how you face up to it once it’s been laid bare.

Get real time update about this post category directly on your device, subscribe now.