Previously on The Gay Goods, we have spoken about the backlash to the Australian police Force (particularly New South Wales Police) after the revelation that a police officer, Senior Constable Beau Lamarr-Condon, had been charged with the murder of Luke Baird and Jesse Davies. Afterwards, the New South Wales Police Force was uninvited to march as a unit in the Sydney Mardi Gras.

This was quickly reversed, despite the Police Commissioner Karen Webb’s tone deaf description of the murders as a “crime of passion,”with the only caveat that they march out of uniform. However, even this request was not upheld. The New South Wales Police Float did not feature the traditional police uniform, but this float was accompanied by armed and uniformed officers as a guard.

View this post on Instagram

It was a disturbing response to the criticisms and distrust that has plagued the police’s attendance at Mardi Gras since 1998. It was in the comments on many of these criticisms that we’d receive every so often a (usually white gay or lesbian) bring up the 78ers, the original protesters, as being in favor of police presence at the Sydney Mardi Gras. I thought that they, as a rule, would be opposed.

But it turns out that the truth is a bit more nuanced than that.

Pre-1978 Gay Liberation activism in Australia

On September 19 1970, in an article published in The Australian, came the announcement of the formation of the Campaign Against Moral Persecution (CAMP.) Its goals were to counter negative perceptions of homosexuality and to advocate for law reform. Its founders, John Ware and Christabel Poll demonstrated immense bravery for the time period by not only being interviewed, but photographed in the newspaper. According to Ware himself, on publication of the article: “the media went mad”.

CAMP was the first open public group for gays and lesbians in Australia, but not the first overall. A year earlier, the ACT Homosexual Law Reform Society and the Australian arm of the Daughters of Bilitis (later Australasian Lesbian Movement) were precursors, but they had heterosexual spokespeople and closed membership. CAMP’s formation brought not only numerous branches but also splinter groups with differing views. Chief among these was the Sydney Gay Liberation and the Gay Liberation Front in Melbourne and the CAMP Women’s Association. Although at times strained, cooperation did occur with these groups in the changing of laws and societal perception of homosexuals.

CAMP’s first demonstration outside of the Liberal Party Headquarters on October 8 1971. (Phillip Potter)

Many activist events occurred prior to 1978, starting with the demonstration outside the Liberal Party (Australia’s centre-right major party) in 1971 in support for Federal Attorney-General Tom Hughes after his comments in favor of homosexual law reform. The Gay Liberationists undertook what they called “Zaps.” These were displays in public spaces of homosexual behavior, such as a mass same-sex kissing on public transport.

The First Mardi Gras

After relocating to San Francisco from Sydney, Alison Britton was involved in mass action against the ballot proposition called the Briggs initiative. The purpose of the initiative was the removal of anyone who supported gay rights from any job within the public school system.

For San Francisco’s Gay Freedom Day parade, conducted on the ninth anniversary of the Stonewall riots, the organizing committee was encouraged by Britton to contact Anne Talve and Ken Davis. Talve and Davis were socialist friends of Britton who were active in Sydney Gay Liberation. Talve and Davis were appealed to conduct a solidarity event with San Francisco, among other international gay community groups.

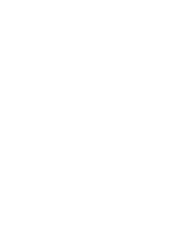

The Poster for the First Mardi Gras at the time styled as Day of International Gay Solidarity. (Chris Jones/State Library of NSW)

The planning of this event was not solely a leftist endeavor. People from gay, lesbian, university politics, socialist, and religious groups collectively planned the International Gay Solidarity event of 1978. The date was set for June 24, with a morning march and public meeting. CAMP’s political action group proposed a late night street party, inspired by the parades in the USA and Europe. The street party was dubbed a “Mardi Gras’ by the co-president of CAMP, Marg McMann. Due to the disparate groups involved, the first Mardi Gras planners and attendees styled themselves The Gay Solidarity Group.

The Permits Were Not Good Enough

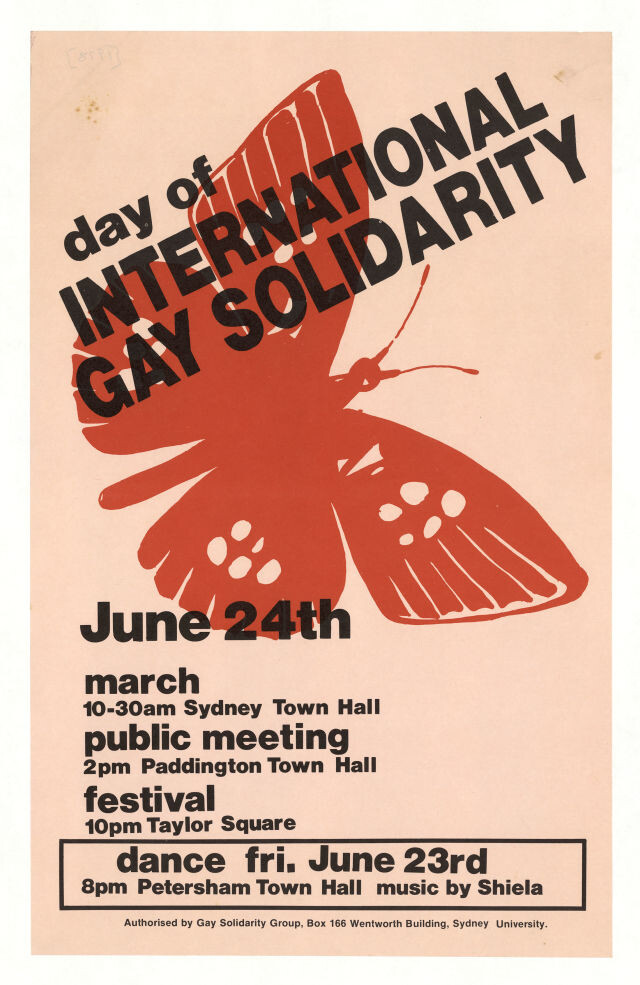

Proud lesbians marching with the Gay Solidarity Group on June 24 1978 during the Solidarity March (Sallie Colechin)

At 10pm on June 24 in 1978, the street party began with protest banners, songs, and chants. 2000 people were believed to have attended. Gay bars came out to support the paraders as they openly defied the shame and marginalization they were facing.

Although street permits had been given for the party, it didn’t stop the police from deciding this was too far. Close to midnight in College Street and Kings Cross, the police began to violently attack the marchers, confiscated a flat-bed truck used to hold the banners, and threw them violently into paddy wagons. Peter Murphy, a gay liberationist and member of the Communist party, stated it best:

“It was a police riot, and the poofters and dykes were fighting back…garbage and garbage bins were flying. I had never seen anything like it, and neither had the police.”

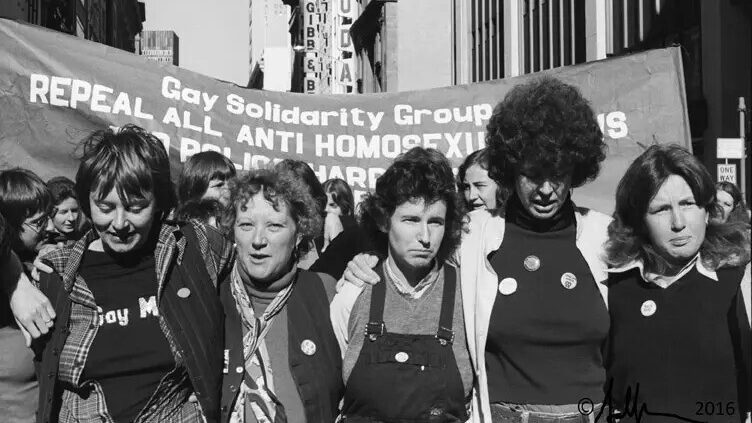

The beginning of the end as police man block exits on Darlinghurst Road on the night of the First Mardi Gras. (Branco Gaica)

You could hear them in Darlinghurst Police station being beaten

After blocking off both ends of Darlinghurst Road, police began punching, kicking, pushing and pulling people along the ground. Indigenous people and sex workers also joined in to resist the police brutality. All in all, 53 people were arrested. According to Ken Davis:

“You could hear them in Darlinghurst Police station being beaten up and crying out from pain. The night had gone from nerve-wracking to exhilarating to traumatic all in the space of a few hours. The police attack made us more determined to run Mardi Gras the next year.” Murphy himself was one of those who were brutally beaten.

Protests at these arrested started the following day at the Darlinghurst Police station, but it wasn’t until the Monday’s publication of the Sydney Morning Herald that stoked the fire of resistance and liberation.

The Publishing of Names

On Monday, June 26 1978, the 53 people arrested had their names, addresses and occupations published in the Sydney Morning Herald. This was catastrophic with most of the arrestees losing their jobs, being kicked out of home and having their rental tenancies terminated. Some even completed suicide.

A “Drop the Charges” campaign by the Gay Solidarity Group was now in operation. On the same day as the publishing of names, 300 protested outside the closed courthouse in Liverpool Street. Seven of the participants were arrested. The following month on July 15 another 2000 people participated in a gay rights march from Martin Place to the Darlinghurst Police Station, with 14 arrests. From the 4th National Homosexual Conference, 300 people marched down Oxford Street and more than a third of the participants were arrested (104). A total of 178 people were arrested in the actions, protests and demonstrations of the Gay Solidarity Group in 1978.

An unidentified protester being taken away by police at the 1978 Central Court protest on June 26 1978. (Fairfax Syndication)

The Aftermath of Names

The events of 1978 truly galvanized lesbian and gay activism in Australia. They united under common goals- ending police harassment, repeal of oppressive legislation and an end to discrimination. Additionally the right of peaceful assembly was a key flashpoint that brought on board solidarity from other civil rights groups including unions, students and progressive churches. These actions eventually led to most charges against those 53 people dropped in April 1979. Sadly not all of them had lived to see this.

The following month, the Summary Offences Act (the legal framework that the police used to arrest the 78ers) was repealed. This was a huge step, as this legal framework had been used overwhelmingly to oppress Indigenous people, sex workers and same-sex attracted people. A more insidious use of this came by entrapping people who frequented beats. (“Beats” are areas common for cruising such as public toilets, car parks and public parks).

Although there was resistance from the community concerned about a repeat of the previous year’s trauma, the second Mardi Gras occurred on 30 June 1979. This time 3000 people attended and the annual tradition of the parade was formed. In March of this year the total number of spectators to the Sydney Mardi Gras Parade was 120,000 with a further 12,500 participating in the parade itself.

Police Marching In Mardi Gras

Police first began marching in Mardi Gras in 1998. 40 LGBT officers marched in uniform, coincidentally also in the year that the 78ers were asked to lead the parade. Since then the police have been involved in the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras both as participants and for crowd control. However all has not been smooth sailing.

In 2013, the brutal arrest of Jamie Jackson Reed by (then) Constable Leon Mixios went viral on YouTube. It took three years of internal investigation before a finding of “unreasonable use of force” was delivered and during his appeal Mixios resigned. During the investigation, Mixios remained a police officer, but was placed on desk duty. A further three incidents occurred at the 2013 parade resulting in the NSW Police coughing up 283,880.75 AUD in damages and 385,903.90 AUD in legal costs.

Barbara Karpinski and the offending poster at the Sydney Cricket Grounds watching the 2022 Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras. (Barbara Karpinski)

In 2022, Barbara Kapinski, a 78er and arrestee on the night of June 24, was ejected from the Sydney Cricket Ground Stadium while she was watching the 2022 parade because of her handmade poster condemining Vladimir Putin. Although the NSW Police swiftly apologized, Karpinski was traumatized. It reminded her of the events of her teenage arrest.

After the initial invitation was revoked for the police’s participation in Mardi Gras this year, many members of the LGBTIQ community rushed to the defense of the police, including 78er Julie McCrossin AM.

One of the arrestees of the night of June 24 1978, McCrossin made the following statement on her X account:

Very sorry Sydney Mardi Gras has withdrawn the invitation for NSW Police to march with us at the Sydney Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras Parade this weekend.

NSW Police have marched for 20 years and attended many other Mardi Gras-related events. Some of these police are Gay & Lesbian… pic.twitter.com/SQahMgkk20

— Julie McCrossin AM (She/Her) (@JulieMcCrossin) February 26, 2024

McCrossin and Krpinski were both there

But although people rushed to use McCrossin’s comments to support the police presence, equally some 78ers disagreed. Karpinski wrote an open letter in the Sydney Morning Herald stating that “trust is broken.” Although she had “welcomed the police marching in previous years…this year there should be no cops at Mardi Gras.”

Now needs to be a time of police reflection…we are not looking for an apology…we are looking for time to heal, and for the police to use that time wisely to take steps to ensure police accountability is not overseen by the police themselves.

When I asked the First Mardi Gras Inc., who now operates as the membership organization for the 78ers, about any unified comments on the situation of police presence I was foolishly under the illusion that there would be an overwhelming and unified backlash. Co-chair Robyn Kennedy explained to us via email:

78ers have diverse views on the issue of police presence in the parade. First Mardi Gras has no control over statements made by individual 78ers even if those individuals are members of our organization.

RELATED LINK: Flip, flop, fucking hell?: Sydney Mardi Gras board uninvite then reinvite NSW Cops to Parade

Words from First Mardi Gras Inc Themselves

This surprised me considering the statement made by First Mardi Gras Inc. in response to 2022 findings of Justice Sackar over unsolved anti-LGBTIQ hate crime deaths between 1970 and 2010:

First Mardi Gras Inc…is particularly concerned that the NSW Police position is indicative of a continuing resistance to the transparency of police operations and an insensitivity within the force towards issues of profound importance to the LGBTQI* community.

When the Police Commissioner Mick Fuller apologized to 78ers and the LGBTQI community for the behavior of police in 1978, there was genuine hope that cultural change might be underway. That was in 2018 and since then the community has seen little evidence that this change runs deep.

The Mardi Gras board’s reversal of the decision to allow police to march was met with equal praise and scorn. The leftist Pride In Protest condemned the decision, whereas the NSW Premier Chris Minns was overall supportive.

Where do we go from here?

It’s clear to myself now that the 78ers are cooperative to each other. But, due to the variety of politics and goals of the initial Gay Solidarity Group, there can be no consistent unified view. That is not a bad thing at all. It just means that the 78ers’ opinions and experiences will be nuanced. To brand them as a whole as opposed or in favor of police presence is myopic and disrespectful.

I myself clearly was blind to this and I apologize wholeheartedly to the 78ers for misunderstanding the diversity of their positions.

One of the many arrested on the night of the First Mardi Gras was Gail Hewison (far left). (Mirror Australian Telegraph Publications)

So if the use of the 78ers as an pro/anti-police argument is ineffective, what is?

My question to anyone on this issue is this: what were the initiating factors that encouraged the First Mardi Gras? What were the goals of the subsequent protests and demonstrations after the arrests of the 53 people on June 24, 1978? Have the goals of these protests been achieved? If they haven’t been, what does that say about the presence of police in uniform? What does it say about police presence out of uniform?

Our arguments must be drawn from data, not from opinion. I have my opinion, I have my biases. I strive to be open to data that counters my current theories. We must, however, always be critically assessing our theories. In this case I was flippant, and so were my fellow gays. And we are both wrong.

Sources: CityHub, First Mardi Gras Inc, Freedom Socialist Party, The Guardian, Instagram, It Was A Riot!, The Leader, O&G Magazine, Pride In Protest Podcast, Scrapbook of Newspaper Clippings by Digby Duncan, Solidarity.net.au, Star Observer, Sydney Gay And Lesbian Mardi Gras, Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras 1978-2022 Interactive Timeline, The Sydney Morning Herald, X

*-this ordering of the acronym is reflective of the statement made by First Mardi Gras Inc.

Get real time update about this post category directly on your device, subscribe now.